One of the fundamental insights of the Strong Towns movement is that in the 20th century we built vastly more public infrastructure than our tax base can support long-term maintenance on. Too much of our shiny and new development is actually low value per acre and for the amount of public investment required to support it. We call this “doing the math.”

For example, a developer comes to your town to build a new cul-de-sac carved out of a farm on the suburban fringe. In exchange for the right to build twenty houses they will build all of the public infrastructure to support them: roads, pipes, power lines, fire hydrants, etc. and then hand that over to the town. The town gets a free road and a bunch of new tax paying houses—growth! Tax receipts go up and the town uses them to pay for more and better schools, parks, public buildings, police, fire, etc. However, the long-term maintenance cost of repairing the roads, pipes, lines, etc. cannot be supported by the low tax revenue per length of road, pipe, line etc. Every thing is great for the first 30 years, but then the road needs to be repaved, the pipes lined, the sidewalk starts looking shabby.

Roughly speaking, public infrastructure needs can be understood as a function of intensity of service, amount of private investment, and land area. Bigger sites have more road fronting them, longer for pipes and wires to travel, etc. Higher demand uses create more demand for wider roads, bigger pipes, and fatter wires. A city or town should, in general, be looking to get the best value per acre. After all the city’s or town’s most fundamental resource is its land. Are you using it well? Are you getting a good return in tax revenue on your public investments? You might be surprised at how properties stack up.

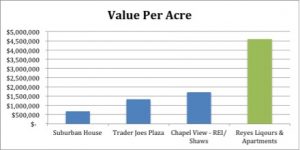

For example, here’s a typical house in a suburb outside of Providence, assessed value $305,000, on a almost half-acre lot; value per acre: $664,782 per acre.

A run of the mill strip mall, like where you’d find a Trader Joe’s, is worth a lot more of course, assessed value of just over $9 million, and on 6.88 acres of land, it’s worth about $1,317,572 per acre; about double our single family house—though Bald Hill Road is certainly more than double the public infrastructure than the quiet residential street.

A more upscale retail destination, such as this portion of the Chapel View shopping center, does better, at 10.78 acres and an assessed value of $18.5 million, it clocks in at $1,716,141 per acre.

But I’d like to contrast these shiny, prestigious properties with a much more hum-drum building: a little, run-down mixed-use building on the west side of Providence, with a liquor store on the ground floor and a couple of apartments upstairs.

At an assessed value of just $321,500 it doesn’t seem impressive. But it creates that value on just .07 acres, meaning that it has a value per acre of $4,592,857, more than two and a half times the value, per acre, of the prestigious Chapel View shopping center!

In other words, if you’re looking to get a better rate of return on your city’s public infrastructure investments, you would better off building lots of little Reyes mixed-use multifamily buildings, than big shiny new shopping centers.

One of the reasons (though hardly the only one) our cities and towns always seem broke is that we keep building expensive public infrastructure for low value private investment, and the tax revenue doesn’t keep up. The suburbs may seem shiny and new, but after that first gloss of new development wears of, the decay sets in. Good cities are built frugally, incrementally, ensuring that we get the best return from our communal public investment.

as a (retired) math teacher I love this example, I wish I had thought of it while I was still teaching.

Such calculations were the basis of the origin of Grow Smart RI started by the head of the Providence Gas Company who did the math of what it cost to put in gas pipelines in low density suburbs. But Prov Gas is now part of (non-) National Grid which not only absconded from downtown Providence, last I tried you cannot even pay a Grid bill downtown. And Citizens Bank is moving much of its work force from the metro area out to the boonies requiring extending infrastructure – the state, rolling over, is even building them a new I-295 interchange to facilitate the move, that without significant protest.

Not sure if there is any point struggling on this any longer.

The economics of development is more than just assessed value per acre. As a (retired) financial analyst, I would argue that it is a function of money out and money in – Rate of Return, or ROI – and on that basis the Rayes Liquor building isn’t just more attractive than the other examples, it is more attractive by an order of magnitude!

The incremental expense to a municipality to support in-fill development like Rayes in a neighborhood that already has roads and utilities – the marginal cost – is almost nothing, but the incremental revenue it receives, the difference between the tax revenue from the property after construction vs. the value before – the marginal revenue – produces a huge ROI because the “I” is so small.

The marginal cost of the shopping center is not only higher utility infrastructure and road frontage costs, but the cost of bigger roads to support the traffic that shopping centers generate and the stress on drainage systems from their large parking lots. The marginal revenue is only the tax on the box stores and parking lots, excluding the land – far less than the total assessed value.

Low density residential development – detached single family homes on large lots – is the worst investment of all. Not only are road and other infrastructure costs so much higher per acre (and per capita), but the low density ensures that the only way to get around is by car (note the lack of sidewalks), and the only way kids can get to school is by bus, adding significantly to marginal cost, and virtually ensuring a negative ROI.

Citizen’s Bank is a classic example of how far off the rails public policy can go. I’m sure that Citizens threatened the Raimondo administration with the prospect of relocating out of the State if it didn’t support their move to the boonies, and fearing criticism for not being focused on jobs, it agreed. However, if the administration had simply compared the ROI of this move to a site that didn’t require the enormous infrastructure investment (and maybe even offered employees the option of taking transit rather than paying $8,000 a year to commute by car), it could have offered Citizens an impressive package of incentives that would have been more cost-effective. The economics are so compelling that it is well worth keeping up the struggle!